THE SOMERSETT SITE

An archaeological portrait of an Ulster-Scots habitation on the Maine frontier

PAMELA CRANE

The following pages are reproduced from: “1718-2018, Reflections on 300 years of the Scots- Irish in Maine”

printed following the academic conference held at Bowdoin College, Maine in August 2018.

© 2019 Maine Ulster-Scots Project and the Ulster-Scots Agency

PART 5

Food Consumption and Production

The McFaddens gathered, hunted, fished, and cultivated native plants and animals. They also raised and cultivated Old World meat, poultry, and garden crops. Taken as whole, they had a rich and varied diet. Dietary information was gained archaeologically from ceramics, animal bone, seeds, and pollen. Nancy Asch Siddel, Archeobotanical Consulting, identified the seeds and Dr. Naomi Riddiford, of Harvard and the University of Reading, analyzed the pollen. Of particular importance, the pollen was from a sealed context: it was collected from the cellar floor which had been capped by burning timbers during the raid in 1722, and then covered with sediments from the cellar berm.

Beaudry, Long, Miller, Neuman, and Wheelery performed an exhaustive study on ceramics from tidewater Virginia and Maryland. By going through probate records and other contemporary documents, she compiled a list of the kinds and purposes of different ceramics vessel types.(16) Pieces of a complete jar were found on the cellar floor. The jar was made in North Devon in the West of England.(17) It stands 33.5 centimeters tall and has a capacity of 12.8 liters, just over 3 U.S. gallons. These vessels were used to make and store sour cream, clabber, and butter.(18) The vessel provides direct evidence that dairy was a part of their diet. (Figure 10)

Figure 10

The many pieces of this North Devon butter jar were found at the level of the cellar floor, indicating it was in storage there at the time the house was destroyed. Note that the vessel is inverted in this photograph, as the restored vessel was not sturdy enough to sit right-side-up.

Only a single artifact was found relating to food consumption. This is a redware drinking cup, possibly made in the English midlands. The cup was finely potted with thick, black, shiny–almost iridescent–glaze. Squat in shape, it measures 7.0 cm of overall height and has a capacity of 16 ounces. The cup has a loop handle below the rim.(19) (Figure 11) Because this was the only serving utensil found, it may be the McFaddens used wooden trenchers or bowls.

Figure 11

Black glazed redware drinking cup found in the cellar.

From the pollen analysis, wild foods available to the McFaddens included chestnuts, walnuts, hickory nuts, hazelnuts, wild plum, highbush cranberries, and blackberries. Bones of deer, three species of wild duck, and sturgeon were recovered during the excavations. There was one very small fish vertebrae, possibly herring or some other small fish. Domestic animal remains included egg shell, pig digits, a cow or beef scapula. The scapula is small, either from a breed or a young animal.

Several pieces of a single cast iron cooking pot were uncovered (Figure 12). These include the body, rim, and the two lugs holding the two ends of the bale. The lugs are straight and not rounded; the tops of the v-shaped lugs are parallel to the pot’s rim. These attributes date the cooking pot to the seventeenth century.(20)

Figure 12

Cast iron cooking pot, pieced together from fragments recovered from the cellar floor.

(Photography courtesy of Brad McFadden)

Table 1

Old World Food Plants Cultivated at Somersett

Evidence of the crops that they were growing comes from the pollen analysis seed identification, and is only identified to family.(21) The broad categories included the carrot, cabbage, and grains. Squash and sunflower were certainly introduced by the local Norridgewock or other Wabanaki tribes, or from neighboring New Englanders familiar with these foods.(22)

Also present was a number of salad or pot greens, native to Europe. While lettuces are commonly eaten today, others are now considered as weeds. These include purslane, nettles, and goosefoot. These were eaten as a matter of course by country folk, but during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the gentry had a mania for wild greens.(23)

Goose foot merits further discussion. Chenopodium, a genus of the Amarath family, encompasses a large number of species present in both the Old and New Worlds. These plants produce numerous starchy seeds; one family native to the Andes of South America, C. quinoa, is more familiarly known as quinoa. The seeds of a variety native to Maine, C. berlandiei, were identified in antiquity at the Norridgewock Village site, as well as winter squash, corn, and sunflower. Because Chenopodia require open sunny settings to thrive, it would have been present in the forested area to which the McFaddens arrived. They may have obtained seeds from the local Wabanaki. More likely, the McFaddens brought seeds to Somersett as fodder for poultry, or pot herbs or salad greens.(24)

Medicine

The only artifact directly related to health, was the base of a mouth-blown medicine bottle. Of pale blue glass, it has a glass-tip pontil scar, a shallow kick-up, and a diameter of 3.6 centimeters.(25)

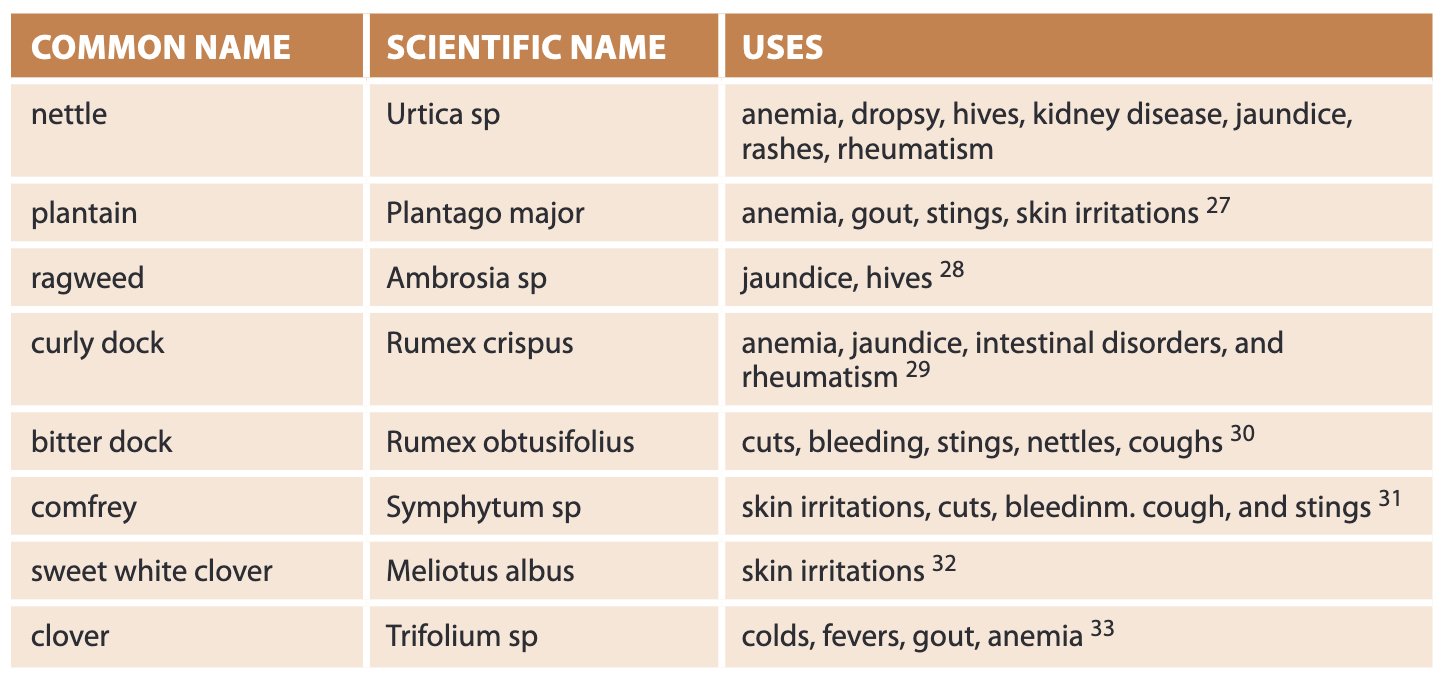

A minimum of eight medical herbs were identified in the pollen and seed samples. These may have been chewed, or made into poultices, salves, syrups, and teas. Often, they were combined herbs, butter, lard, oil, and spirits.(26) The number and variety of uses indicates a significant level of expertise that would have been invaluable on the frontier.

By its very name, “aqua vitae,” or “water of life,” distilled spirits were thought to promote health and were medicinal in nature. Indeed, gin was first sold in chemists and apothecary shops, and later in establishments catering to the “basic, visceral human drive for intoxication.”(34) Medically, distilled spirits were ingested directly, applied topically, or used as base for herbal ingredients.(35)

table 2

Medicinal plants cultivated at Somersett

Tobacco Smoking

Alaric Faulkner referred to the history of tobacco smoking as the “democratization of a bad habit.”(36) Christopher Columbus’ crew observed the Indians of Central America inhaling tobacco smoke through a pipe shaped like a “little ladle.”(37) By the mid-sixteenth century, tobacco smoking was reserved to the upper classes; there is a charming anecdote that a man cleared the streets by, “emitting smoke through his nostrils” in a dragon-like fashion.(38) And by the beginning of the seventeenth century, the tobacco habit had spread to the gentry and masses alike.(39) Exports from Virginia to Britain jumped from 60,000 pounds in 1622, to 22 million in 1693.(40) Ian Walker estimated an average consumption of four per household per week in eighteenth-century England.(41)

Tobacco pipe fragments are cherished by archaeologist for many reasons. They are fragile and easily broken, so they are present in great numbers on most archaeological sites. Because the rapid formal and stylistic changes over time, they can be used to date a site to some specificity. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they were made mostly in Britain and the Netherlands, but shipped world-wide thus, they offer information on global trade patterns. Bristol pipemakers produced most of the pipes exported to the American colonies, shipping “literally thousands of gross of pipes” from the port of Bristol.(42)

While tobacco pipes may date a site by a statistical analysis of the interior diameter of their stems, it requires a large sample to calculate an accurate date. To date, we have collected 117 stems to assess the date of the Somersett site. A more useful way to obtain a date range for the site is by the shape of the bowl, the decoration on the bowl and stem, and stamped makers’ marks on the bowl, heel, or stem of the pipe. Over time, pipe scholars have amassed considerable amount of data on individual pipe makers, their dates of operation, and their trade marks.

There is a single stem with the elaborate rouletting (Figure 13). A partially legible maker’s mark reads “DOESBUR...”. The word seems to be Dutch, as there is a Doesburg located at the confluence of the Rhine and IJessel Rivers in the Netherlands. Whether this pipe was manufactured in that city or manufactured by a person of that name, either in the Netherlands or somewhere in Britain, has yet to be discovered.

Figure 13

Marked tobacco pipes from the Somersett Site cellar. a: bowl fragment marked with the name R. [Robert] Tippet. This example was manufactured by the second (active 1678-1722) or third (active 1713-1715) of a family of three Bristol pipe makers, father, son, and grandson.

b: Pipe stem fragment marked with a common toothed rouletted pattern and the unidentified maker’s mark “DOESBUR...”.

The most common pipe bowl-type found on the site is the funnel-elbow. These lack a resting point, that is they are without a heel. These bowls are unmarked and roughly date from 1700 to 1820.(43)

There are several funnel-elbow pipes stamped “RT,” on the back of bowl; some of these have an additional mark on the side, “R/TIPP/ET,” stamped incuse (Figure 13). The mark pertains to three generations of pipemakers belonging to the Tippet family and working in Bristol. Robert Tippet was active between circa 1660 to 1680, Robert Tippet II between 1678 and 1722, and Robert Tippet III between 1713 and 1715.(44) The form and maker’s mark date these are pipes nicely from 1700 to 1722. These pipes have been found on several archaeological sites in Maine, including Fort Richmond, Norridgewock, and Fort William Henry at Pemaquid.(45)

Finally, there are three funnel-elbow pipebowls with resting points. These pipes carried the initials “W” and “G,” stamped on either side the heel. The initials are read with stem facing the smoker, so that the given name faces left and surname faces right. These may be ascribed to William Goulding, 1 and 2. They cannot be dated as tightly, but examples were recovered from Fort Frederick at Pemaquid.(46)

The pages above are reproduced from: “1718-2018, Reflections on 300 years of the Scots- Irish in Maine”

printed following the academic conference held at Bowdoin College, Maine in August 2018.

© 2019 Maine Ulster-Scots Project and the Ulster-Scots Agency

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright holder.

Read more and order the 256 page book at: https://www.maineulsterscots.com/reflections